How My First Pow Wow Deepened My Understanding of Protecting the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Watershed

By Kai Abreu

The drums shook the ground beneath my feet, each beat vibrating in my chest. Singing echoed throughout the park as visitors quickly flocked to the sitting areas. Dancers in regalia formed a line through a roped entrance into a space where drummers and singers sat together under a tent. The vibrancy of their outfits contrasting with the gloomy day. I stood quietly off to the side, listening to instructions given by the Master of Ceremonies (MC). This was my first pow wow ever, and really, my first experience learning first-hand about Indigenous cultures.

As someone who comes from a place where Indigenous communities and cultures were largely spoken about in an exclusively historical context, a tight-lipped “this happened then and there and that was that” one-sided conversation, I was eager to actually learn from the Peoples themselves.

The See Muskoka Through Our Eyes Pow Wow in Bracebridge, Ontario, hosted by the Parry Sound Friendship Centre, provided this opportunity. I was invited to attend the event as part of the Biinaagami team; my second event, inviting people to explore the beautiful Giant Floor Map of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed. I’m grateful for the invitation, as it expanded my knowledge of the land I now live on, but it also gave me a deeper understanding of our shared responsibility to protect our waters.

What is a Pow Wow?

Not too long ago, I had no idea what a pow wow was. I’d heard the word here and there, but never really had any context for it. In case you’re in the same boat, the basic definition of a pow wow is a social gathering and celebration of Indigenous culture. It has a few different interpretations across Canada and the U.S, but it’s generally viewed as a celebration. Pow wows sometimes feature ceremonial songs and dances, so it’s best to attend the event with some knowledge of the appropriate etiquette. But when in doubt, look to the Elders and follow their lead.

The exact origin of pow wows remains unknown, but many Indigenous communities across North America adopted and adapted these celebrations throughout the 20th century. According to an article by the Canadian Encyclopedia, “With the introduction of reserves in the 1830s, First Nations in both Canada and the US attempted to resist cultural assimilation by maintaining a connection to Indigenous traditions through dance and music.” (Simpson and Filice). Today, pow wows continue to serve as a space for preserving and sharing Indigenous cultures. Some pow wows remain private, intra-national events, reserved for particular First Nations communities, and some, like the Bracebridge Pow Wow, are public gatherings that invite all to come and share in the experience.

Pow wows, though adapted with differences across nations, generally require several different roles, from Head Staff (including the MC) to the host drum group to male and female lead dancers of each dance style.

As our work at Biinaagami is rooted in Indigenous knowledges, I looked forward to attending an event where I would experience these knowledges first-hand by listening to the stories of the participants. I still have much to learn, and I look forward to doing so, but this first pow wow will remain a truly unforgettable experience that helped me understand the sacredness of connection and its importance in protecting our shared waters.

An Observational Learning Experience

Grand Entry

The first thing I noticed arriving at Annie Williams Park in Bracebridge, was the welcoming and inclusive atmosphere. Everyone we passed welcomed us with a smile as we walked down to an open area to set up our Biinaagami map. Dozens of vendors and a few food trucks set up near us. The scent of something sweet tickled my nose and the vibrant crafts of various vendors caught my attention. Shortly after everyone settled in, Grand Entry began, with dancers, the Eagle Staff carrier and flag carriers quickly lining up — ready to enter the dance arena.

Flags of a few local First Nations, municipalities, and organizations buffeted proudly in the cool wind. The MC announced the beginning of the celebrations, and powerful drums crackled the air. Dancers of all the different styles began circling the tent that sheltered the two drum groups: White Tail Cree and SpiritWolf. Soon, colour and beautiful song engulfed the park. After the Flag song and the Veteran’s song, Grass dancers, as always, would have the first dance — a traditional custom where the men’s quick and powerful footwork flattens the grass for the following dances.

The MC introduced each flag carrier and the flags they held. Most of them I had never seen, including the flag for the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation and Mattagami First Nation. One of them did seem familiar though — a rainbow Pride flag with two black and white feathers. I knew Two-Spirit was an Indigenous-specific word used by some members of the community to self-identify as someone combining or transcending masculine and feminine roles or characteristics. However, I hadn’t seen the flag in person before.

Two-Spirit Pride flag. Sometimes the Two-Spirit Pride flag will feature a Progress flag behind the feathers. In 2024, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights and Day of Pink revealed a new Two-Spirit flag designed by Patrick Hunter.

Sure, I’d joined the massive, sweltering summer event of Pride in Toronto, a beautiful and incredible celebration of diversity in its own right, but this was different. This didn’t feel like only a celebration, but it felt sacred. In those long moments where the flag was proudly held up in the sky, songs filling the space, drums electrifying the air, it felt like not only the Two-Spirit community, but each community represented by the various details of the flag, were held in reverence. As I watched the flags go round and round, I understood why pow wows were considered healing ceremonies — as much as an outsider could. I felt a deep sense of gratitude wash over me. I had been invited to this space to witness something deeply sacred with a welcoming and inclusive spirit I had rarely experienced before.

Connected People and Connected Waters

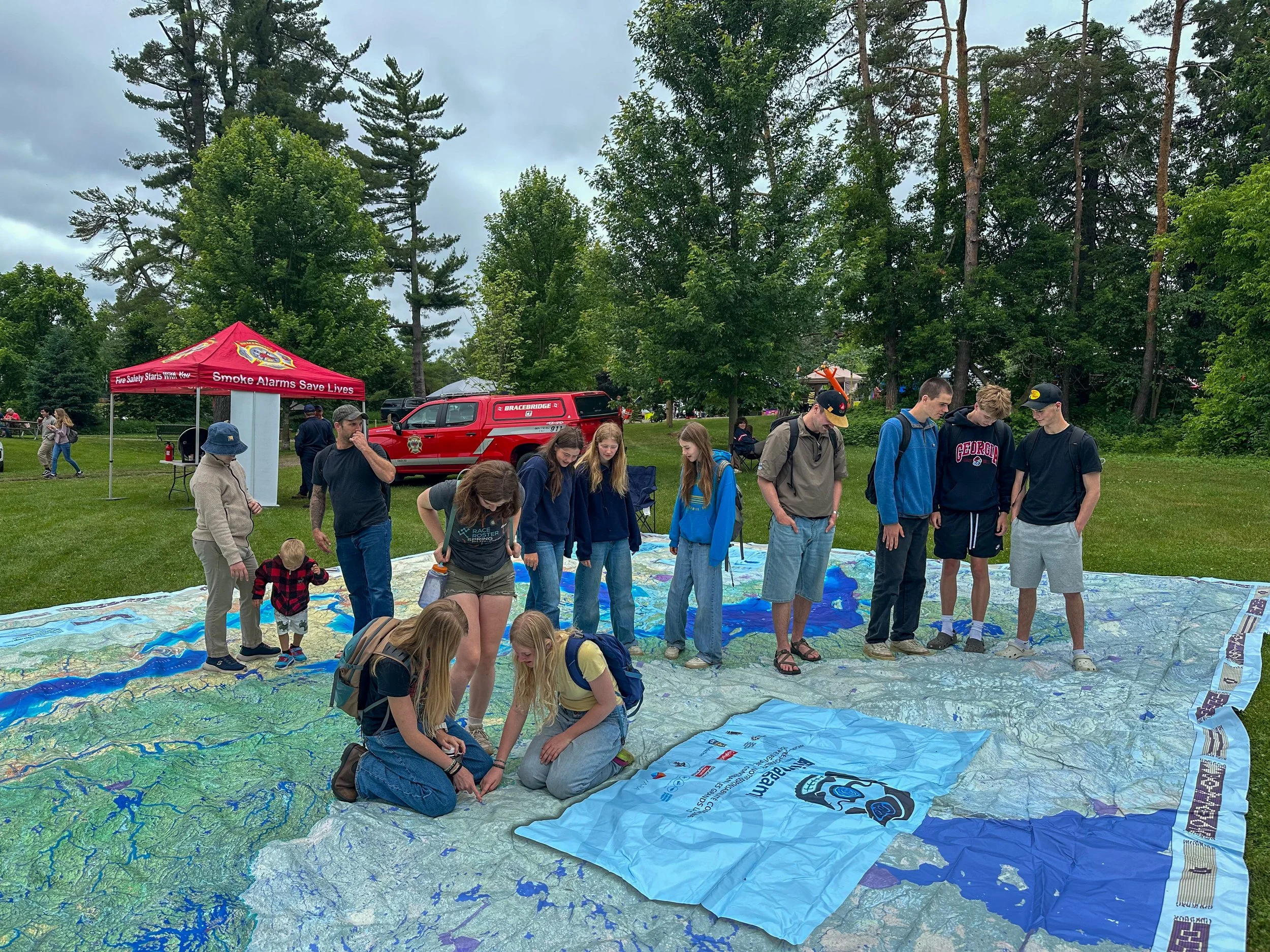

The sense of inclusivity continued through the day as more and more people visited the Biinaagami map. Folks from all over attended the pow wow, and many eagerly shared their water stories with us. A couple from the area recounted their many trips up and down rivers throughout the region, staying in public spaces. Campgoers told of their several hundred kilometers trips on rivers from not too far north of Bracebridge, all the way up to Hudson Bay, a completely different watershed. Families from Sweden and Finland shared stories of their own lakes back home, of how important these waters were to them. Singers and dancers from the pow wow traversed the map as well, finding the waters that represented home to them.

I had the privilege of engaging with all of these people in meaningful conversations about water. They spoke with passion and love about lakes and rivers that shaped their childhoods, that had provided a place of peace and joy for their families for generations. Many members of local Indigenous communities offered me more context and background to the stories we share through Augmented Reality on the map.

People exploring the Biinaagami map at the Muskoka Through Our Eyes pow wow in Bracebridge, ON, 2025. Photo courtesy of Kai Abreu — Biinaagami.

I may have attended this event to educate folks on our mission as Biinaagami, but admittedly, I learned a lot more from them. With each story shared, the map transformed in my mind into a living, breathing thing. Our watershed was no longer an amalgam of lines and water flows, but a friend, a guardian, a provider — a being I felt deeply connected to, protective of and grateful for.

I understood why, as we always say at Swim Drink Fish, connection leads to protection. Through the stories shared, I felt connected to all of the people around me. The people whose land I stood on, who had so graciously invited me to learn more about their culture, but also the people from across the Atlantic Ocean. I could see how our waters connected all of us. On a physical level, the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Watershed flows into the Atlantic, feeding into countless water bodies around the world, but I also felt connected on a different level — connected as people who rely on water for every aspect of our being. We rely on it for sustenance, but we also rely on it for joy, for peace, for a reminder that we are not just on this planet but a part of it.

Hence, our shared responsibility to protect it. Our responsibility is to keep it clean so that people, and every living creature we share the waters with, can prosper in good health. Our responsibility is to heal the waters from the damages that have been done and fervently protect them from any further harm. Our responsibility is to take accountability. We are all part of these waters. Without them, we can’t survive, and without our help, they won’t survive forever either.

An Invitation

I am still on my learning journey. I will be on it for many many years. Today, however, I encourage you to start yours or take a new step. Pow wows offer an incredible opportunity to learn more about local Indigenous communities. Consider attending one near you. The Northern Ontario Travel Magazine keeps an annual Ontario Pow Wow Calendar. Powwows.com shows some pow wows searchable by province or state.

I also encourage you to learn more about the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed through Biinaagami. You can access a virtual map that shows all of the water flows in the watershed and highlights several Indigenous Reservations across the area.

Our waters connect all of us, and they need our help. Whether you live in this watershed, or one across the globe, the responsibility to water remains the same: protect their life and health as they have protected ours for time immemorial.

Note: If you would like to request the Biinaagami map for your event, please contact us. If you would like to have the map at your school, you can request it here.